Breast cancer

- What is breast cancer?

- What are the types of breast cancer?

- What are the symptoms of breast cancer?

- What causes breast cancer?

- What are the risk factors for breast cancer?

- How is breast cancer detected and diagnosed?

- What are the stages of breast cancer?

- What are the treatments for breast cancer?

- What is the outlook for breast cancer?

- What does it mean to live with breast cancer?

- Featured breast cancer articles

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in the United States, followed by lung cancer, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, melanoma (a form of skin cancer), and bladder cancer, according to the National Cancer Institute. Nearly 300,000 new cases of breast cancer are diagnosed in the U.S. each year, with nearly 44,000 deaths.

Finding out you have breast cancer can bring a range of emotions, from anger and sadness to fear and anxiety. But learning more about the disease—including symptoms and risk factors, treatment options, and what it means to live with breast cancer—may provide a sense of reassurance and even empowerment as you navigate your cancer journey.

What is breast cancer?

Breast cancer occurs when cells in your breast tissue grow abnormally. These abnormal cells divide and replicate quickly and may form masses called tumors.

Cancer cells and tumors may emerge from different parts of your breast, so it helps to understand the organ’s three main parts:

- Lobules are glands that make breast milk.

- Ducts transport breast milk from the lobules to the nipples.

- Connective tissue consists of fibrous tissue that supports and protects muscle and breast tissue, as well fatty tissue that fills the space between fibrous tissue and glands in the breast.

Breast cancers often start in a duct or lobule.

What are the types of breast cancer?

Breast cancer types describe where cancer originates and whether cancer cells have spread beyond this starting point. Cancer can move beyond the breast through your blood and lymph vessels in a process called metastasis. (Lymph is a fluid that consists of immune cells that help fight infection. It flows through a network of vessels in the body and is stored in small structures called nodes.)

Cancer that hasn’t spread from its original location is called in situ, meaning it has stayed in place and is considered noninvasive. When cancer cells spread into surrounding tissue, it’s considered invasive breast cancer.

Types of breast cancer include:

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

DCIS is a noninvasive breast cancer. Abnormal cells are limited to your breast ducts and haven’t spread into other breast tissue.

Lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS)

LCIS grows in lobular glands. Abnormal cells haven’t infiltrated tissue outside of the gland. Some experts consider LCIS to be precancerous, while others don’t consider LCIS a true cancer since these cells are confined to lobular tissue.

Invasive (or infiltrating) lobular carcinoma (ILC)

ILC makes up 10 percent of breast cancers. ILC starts in a lobule and then spreads to other tissue inside and possibly outside of the breast.

Invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC)

IDC is the most common type of breast cancer. It accounts for 50 to 70 percent of all invasive breast cancer types.

IDC starts in a breast duct but spreads to other breast tissue. Cancer cells can then infiltrate tissue outside your breast, such as in nearby organs. Some cancers have features of both invasive ductal and invasive lobular carcinoma. This rare subtype, known as mixed IDC-L, accounts for an estimated 3 to 5 percent of invasive breast cancers.

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC)

IBC is a rare but aggressive type of breast cancer, accounting for 1 to 5 percent of all breast cancers. (An aggressive cancer is one that grows or spreads quickly.) Most inflammatory breast cancers fall under the IDC umbrella since they usually start in a duct. In about one-third of IBC cases, cancer cells have already metastasized to distant parts of the body by the time of diagnosis.

IBC causes the breast to look and feel inflamed due to cancer cells blocking lymph vessels. You may also experience swelling of the skin of the breast and of the lymph nodes in your axilla (armpits) or near your collarbone, and redness or discoloration may cover more than one-third of the breast.

Your nipple may also appear inverted or retracted and the skin of your breast may look pitted or thick like an orange peel. Unlike most other forms of breast cancer, IBC doesn’t usually produce breast lumps. Your healthcare provider (HCP) may therefore not see cancer cells on a breast X-ray called a mammogram.

Angiosarcoma of the breast

Angiosarcoma is a rare form of cancer that forms in the lining of blood vessels or lymph vessels and may appear in the vessels of the breast. It accounts for only 0.1 to 0.2 percent of breast cancers. It may appear as a patch of thickened skin on the breast, a discolored rash or bruise, or as a lump. It can occur in patients who have never been treated for breast cancer, though in some cases it may be associated with previous radiation treatment.

Paget disease of the breast

This cancer type starts in a breast duct and spreads to the skin of the nipple and the area around the nipple called the areola. Around 80 to 90 percent of the time, Paget disease is found alongside DCIS or IDC.

Phyllodes tumor

These rare breast tumors form in connective breast tissue. More than half of all phyllodes tumors are benign (noncancerous) while around a quarter are malignant (cancerous); the remainder are considered borderline.

Rare forms of invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC)

Tubular and mucinous tumors account for roughly 2 to 3 percent of breast cancers. They are usually “low-grade” tumors and often have a better prognosis (or outlook) than the more common type of IDC. Medullary breast cancer accounts for less than 5 percent of breast cancers, and similarly has a better prognosis than other types of IDC.

What is triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)?

Triple-negative breast cancer is a rare and often aggressive type of cancer, accounting for 10 to 15 percent of all breast cancers. Its name comes from the way in which it lacks three common breast cancer biomarkers (characteristics that ordinarily indicate the presence of cancer) in its cells. Triple negative breast cancers may be invasive lobular carcinomas or invasive ductal carcinomas.

Most breast cancers—roughly 2 out every 3—grow under the influence of the hormones estrogen and progesterone. These types of cancers produce positive results when tested for proteins located on estrogen and progesterone receptors (ER and PR) on the tumor. These cancers are therefore known as hormone receptor-positive (HR+) breast cancers.

Triple-negative breast cancer, on the other hand, tests negative for these ER and PR proteins. It also has little to no human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) protein, which is a characteristic of other breast cancers. (Having too much HER2 ordinarily promotes the growth of cancer cells.)

These unique features of triple-negative breast cancer make it harder to treat because conventional therapies that target hormone receptors and human epidermal growth factor receptors on tumors are less likely to be effective.

What are the symptoms of breast cancer?

Breast cancer symptoms can vary, depending on the type you have and whether breast cancer cells metastasize (or grow beyond the breast). You may not always see or feel warning signs of the disease, especially during the early stages of breast cancer.

When they are present, breast cancer symptoms may include:

- Breast pain, warmth, or tenderness

- Changes to the color, shape, size, or texture of the breast or nipple

- Dimpling or puckering of breast skin (sometimes like an orange peel)

- New lump in or near your breast or armpit (although it’s worth remembering that 80 percent of such growths are benign, or noncancerous)

- Nipple discharge (other than breast milk) such as clear or bloody fluid that appears suddenly or in one breast only

- Nipple tenderness

- Nipple that retracts or turns inward

- Red, discolored, swollen, or scaly skin on the breast or nipple that may look like a rash or infection

- Swelling, hardening, or thickening in any part of the breast

What causes breast cancer?

Normal breast cells may become cancerous as a result of changes in genes (called mutations) or due to damage to DNA (the genetic material in your cells). Your body can usually repair DNA damage and keep your cells growing and dividing at a normal pace. But certain harmful gene mutations can cause cells to grow out of control.

Most breast cancers—nearly 90 percent—are the result of gene changes that are not hereditary. That is, these gene changes are not transmitted from parent to child but rather take place during the course of a person’s life as a result of causes that may be unknown.

About 10 percent of breast cancers are linked to gene mutations that can be identified as having been passed from parent to child. Examples of inherited genetic mutations that may contribute to breast cancer include:

BRCA gene mutation

The most common cause of hereditary breast cancer is the BRCA (breast cancer) gene mutation. These include the BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene variants.

In the U.S., only 0.2 percent of people have either variant. Despite its relative rarity, the BRCA gene mutation can raise the risk of ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, and pancreatic cancer in addition to breast cancer.

Carrying either BRCA gene mutation raises the risk of getting breast cancer by 69 to 72 percent, according to 2023 review and analysis of studies published in Cancers. The risk increases with each first-degree blood relative (such as a parent, child, or sibling) who has the disease.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes usually help suppress tumors, meaning they stop or slow tumor growth. But BRCA gene mutations can trigger abnormal cell growth instead.

Other gene mutations

Inherited mutations in other genes can also raise the risk for breast cancer but to a lesser degree than BRCA gene mutations. Like BRCA1 and BRCA2, these genes ordinarily suppress tumors. Mutations to these genes hinder their ability to stop cancer cell growth and division, increasing the chances that breast cancer may develop.

These include mutations to the following genes: ATM (ataxia-telangiectasia mutate), CDH1 (cadherin 1), CHEK 2 (checkpoint kinase 2), PALB2 (partner and localizer of BRCA2), PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), STK11 (serine/threonine kinase 11), and TP53 (tumor protein 53).

What are the risk factors for breast cancer?

Some breast cancer risk factors are outside your control to change, but others may be influenced by lifestyle habits.

Breast cancer risk factors you can’t change

In addition to genetic mutations that raise your risk for breast cancer, contributing factors that are outside of your control include:

- Age: Risk increases with age, and most breast cancers are diagnosed after age 50

- Certain breast conditions: These include LCIS (which is considered precancerous), as well as atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) and atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH). (Hyperplasia is an increase in otherwise normal cells that may become cancerous). Having LCIS raises one’s risk of breast cancer by 7 to 12 times, while risk goes up by 4 to 5 times if you have ADH or ALH.

- Dense breasts: Having dense breasts means you have less fatty tissue and more fibrous and glandular tissue. This raises risk of breast cancer, although it’s not fully understood why.

- Diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure: Taking DES (a medication prescribed in the U.S. between 1940 and 1971 to prevent miscarriage) or being exposed to it while in the womb raises the risk of breast cancer slightly.

- Menstruation: Having your first menstrual period before age 12 and beginning menopause after 55 years of age can expose you to more estrogen and progesterone during your life span. These hormones can cause certain types of breast cancer to grow.

- Family history: Having a first-degree relative such as a parent or sibling with breast cancer can double or triple your breast cancer risk. This may involve genetic variants you inherit, such as the BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations.

- Sex assigned at birth: Most breast cancers occur in people assigned female at birth.

- Height: Taller people assigned female at birth may carry a higher breast cancer risk, possibly due to factors that affect early growth (for example, hormonal and genetic factors, as well as nutrition early in life).

- Personal history: If you’ve had breast cancer in one breast, the disease is more likely to recur in another area of the same breast or in the other breast.

- Radiation therapy: Having chest or breast radiation therapy for another cancer such as Hodgkin lymphoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma before the age of 30 significantly raises breast cancer risk. Teens and young adults whose breasts are still developing carry the highest risk of breast cancer due to this treatment.

Lifestyle risk factors for breast cancer you can change

There are some risk factors that you can influence, including:

- Weight after menopause: Being overweight or obese after menopause causes an increase in fat tissue, which can raise estrogen and insulin levels, hormones that may contribute to cancer growth.

- Consuming alcohol: Your risk for breast cancer goes up with each alcoholic drink, especially if you were assigned female at birth. This may have to do with alcohol’s damaging effects on DNA, the way it reduces your body’s ability to absorb important nutrients such as folate, the way it may increase levels of estrogen in the body, and the way it may contribute to weight gain.

- Taking hormones: Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), also called hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or hormone therapy (HT), consists of taking estrogen and progesterone to replace levels that naturally decrease over time to ease menopause symptoms such as hot flashes. If taken for longer than five years, these therapies may raise breast cancer risk. Birth control methods that use hormones such as the Pill, shots, and intrauterine devices may also increase risk, though the link between progestin-only forms of birth control and cancer risk is unclear.

- Sedentary lifestyle, especially after menopause: Getting inadequate amounts of physical activity may affect hormone and inflammation levels, which can contribute to increased breast cancer risk.

- Late or no childbirth and breastfeeding: Never having a full-term pregnancy, giving birth to your first baby after 30 years old, or not breastfeeding raises breast cancer risk. That’s because the experience of having a baby and breastfeeding naturally interrupts the body’s overall lifetime exposure to estrogen and progesterone, hormones that can increase breast cancer risk. What’s more, the experiences of pregnancy and breastfeeding cause breast cells to change (or differentiate) to enable them to produce milk. Some researchers believe that cells that have differentiated in this way may be more resistant to changing into cancer cells.

- Smoking and secondhand smoke: Smoking may raise breast cancer risk in younger women who haven’t reached menopause. Some studies suggest a link between secondhand smoke and breast cancer risk in premenopausal women, but more research is needed to confirm the connection.

- Nightshift work: Working night shifts and being exposed to light at night disturbs your body’s natural circadian rhythms, which can have a range of effects on the body, including disrupting hormone levels. Some research suggests that short-term night shift work may slightly increase breast cancer risk.

Who is at higher risk for breast cancer?

People assigned female at birth carry the highest risk for breast cancer, especially after age 50. Around 9 percent of all new U.S. cases in this population occur before age 45, however. People assigned male at birth account for less than 1 percent of breast cancer diagnoses.

Racial inequities also affect breast cancer risk. White people assigned female at birth have the highest risk of breast cancer, followed by Black people assigned female at birth, particularly those younger than 40 years old. Black people assigned female at birth are also more likely to have triple-negative breast cancer.

How is breast cancer detected and diagnosed?

Many people detect changes in their breasts by routinely checking them for differences in look and feel over time and reporting these issues to their healthcare providers (HCPs).

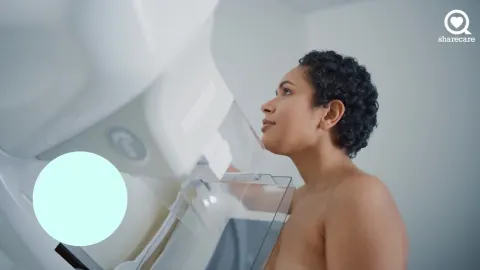

During a physical exam, which may include a clinical breast exam, your HCP may also notice signs such as a lump in your breast or armpit. Breast changes may also be spotted on a routine mammogram to screen for breast cancer.

After discussing results from these exams along with your personal and family medical history and current symptoms, your HCP may recommend further tests to confirm or rule out breast cancer. These may include:

- Diagnostic mammogram to look at specific areas of your breast

- Digital breast tomosynthesis, also called a 3D mammogram, to view three-dimensional images of your breasts (unlike a standard mammogram that creates two-dimensional images)

- Breast ultrasound to produce images of your breast tissue using sound waves

- Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to take detailed images of tissues and structures inside your breast with help from radio waves and strong magnets

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scan to create images of your breast tissue using special dyes injected into your veins

- Blood chemistry test to measure substances such as electrolytes, fats, glucose (sugar), and proteins in your blood that may be indicators of breast cancer

- Skin biopsy, if needed, to remove breast tissue or fluid for further evaluation

If these tests confirm the presence of breast cancer, your HCP will order additional tests to determine the type of breast cancer you have. These include testing for HER2 protein and hormone receptors (ER and PR).

Not all women diagnosed with breast cancer require genetic counseling and testing. But testing for certain mutations known to cause breast cancer, such as the BRCA variants, may make sense for breast cancer patients with certain characteristics, such as:

- Diagnosed at a younger age

- Ashkenazi Jewish descent

- Have triple-negative breast cancer

- Have been diagnosed with a second breast cancer (rather than a recurrence of a first cancer)

- Have a family history of breast cancer, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, or prostate cancer

What are the stages of breast cancer?

If you receive a diagnosis, your HCP will identify the stage of your breast cancer. Along with knowing the type you have, staging helps determine your treatment options.

Tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) breast cancer staging

The TNM system, developed and updated by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), is the most common method used to determine the stage of a breast cancer. In 2018, the AJCC expanded its original TNM system to include information on tumor grade (G), as well as ER, PR, and HER2 status.

To stage the disease, your HCP must know:

- T: What’s the size of the tumor?

- N: Have breast cancer cells spread to nearby lymph nodes? If so, how many?

- M: Have cancer cells metastasized beyond breast tissue into areas such as your brain, liver, lungs, and other organs?

- ER: Are cancer cells positive or negative for the ER protein?

- PR: Are cancer cells positive or negative for the PR protein?

- HER2: Are cancer cells positive or negative for the HER2 protein? If so, are they making too much of the protein?

- G: How much do your cancer cells look like normal cells?

Oncotype DX score

This test scores the likelihood of future breast cancer metastasis and recurrence. The test also helps determine the potential benefit of adding other breast cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy, to your treatment regimen based on whether your cancer is ER-positive and HER2-negative, as well as if cancer cells have spread to lymph nodes.

Location of breast cancer cells

Breast cancer staging also determines whether cancer cells are:

- Localized: This means cancer cells are found mainly in your breast tissue, although a few may have spread to nearby lymph nodes, such as in the armpit.

- Regional: Cancer cells have spread beyond breast tissue to nearby lymph nodes.

- Distant: Cancer cells have spread further to parts of the body such as your bones and organs.

Breast cancer stages 0 to 4 (0 to IV)

The conventional stages of breast cancer are expressed in roman numerals. These include:

- Stage 0 (in situ): This noninvasive, precancerous stage incudes DCIS. Cancer cells haven’t spread beyond the area of the breast where it started.

- Stage I (localized): Cancer has spread from its original site to other breast tissue, but the tumor remains small. Few, if any, cancer cells can be found in nearby lymph nodes.

- Stage II (localized): The cancer has grown to about 2 to 5 centimeters across and either remains in breast tissue only or has spread to lymph nodes in the armpit.

- Stage III (regional): Often referred to as locally advanced breast cancer, cancer cells have spread to multiple lymph nodes, the chest wall, skin, muscle, or other body tissues near the breast, but they haven’t spread to distant tissues and organs.

- Stage IV (distant): This is the most advanced stage known as metastatic breast cancer. Cancer cells have spread to one or more distant parts of the body such as the bones, lungs, and liver.

What are the treatments for breast cancer?

Your breast cancer treatment plan will depend on your breast cancer type and stage, as well as your treatment preferences. These might include:

Chemotherapy for breast cancer

Chemotherapy (or chemo) uses a combination of powerful oral or intravenous (IV) drugs to shrink and slow the growth of cancer cells. If you have a large tumor, this treatment may be given before breast cancer surgery to reduce the size of the tumor and make it easier to remove.

Chemo may also be given after surgery to decrease the likelihood of your cancer returning or when cancer cells have spread to other body parts.

Radiation therapy for breast cancer

Radiation therapy uses high-powered energy beams (such as X-rays) to locate and eliminate cancer cells that remain in your breast, chest wall, or lymph nodes after surgery or have spread beyond breast tissue.

This breast cancer treatment can be performed using:

- External beam radiation: This is the most common radiation method. A large external device aims the energy at your body to eliminate cancer cells.

- Brachytherapy: This involves short-term surgical placement of radioactive pellets inside the body near the tumor site to destroy cancer cells in the area.

Hormone therapy for breast cancer

Hormone therapy, also called endocrine therapy, helps treat breast cancers that are sensitive to the effects of estrogen and progesterone. (Note that this breast cancer treatment is not the same as hormone therapy for menopause symptoms.)

Hormone therapy for breast cancer includes:

- Aromatase inhibitors (AIs): These stop the aromatase enzyme from making most of the estrogen produced by body fat after menopause. The result is to slow cancer growth and decrease the chances of the disease recurring.

- Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs): These block estrogen from binding to breast cancer cells, keeping them from growing and dividing further.

- Selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs): These break down estrogen receptors on tumors by binding to them more tightly than SERMs. SERDs are used mainly after menopause, although they can be combined with other hormone treatments prior to menopause.

- Ovarian suppression: This involves shutting down the ovaries to cut off the body’s main source of estrogen, especially if you’re at high risk for breast cancer returning. Surgery to remove the ovaries called oophorectomy (or ovarian ablation) and drugs known as luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists or analogs are the suppression method most used. The damage to your ovaries caused by chemo might also produce this effect.

- Less common hormone therapies: These include megestrol acetate, androgens such as testosterone, and a form of estrogen called estradiol. Though rarely used, these may be an option if other hormone therapies no longer work.

Immunotherapy for breast cancer

Immunotherapy helps boost your immune system’s ability to locate and eliminate cancer cells and curb cancer cell growth. Immunotherapy differs from chemo.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as the programmed cell death inhibitor 1 (PD-1) pembrolizumab, are immunotherapy medications that work on certain immune cells to help eliminate cancer cells.

Ordinarily, the immune system attacks harmful substances in the body. In addition to cells that attack these invaders, the immune system contains “checkpoint” proteins that help prevent the immune system from damaging otherwise healthy and non-threatening cells.

Breast cancer cells use these checkpoints to prevent your immune system from attacking them. A type of immunotherapy called monoclonal antibodies target these checkpoint proteins to turn your immune response back on so that it can eliminate cancer cells. Rather than acting on cancer cells directly in the way that chemotherapy does, checkpoint inhibitor drugs thus boost your immune system’s ability to find and attack these cells.

Some cancer immunotherapies and checkpoint inhibitors control breast cancer cells in different ways. As such, they’re also considered a form of targeted therapy. These include monoclonal antibody drugs, which mimic the protective antibody proteins made by your immune system.

Targeted drug therapy for breast cancer

Like chemo, targeted drug therapies travel through your bloodstream to reach most areas of your body, including cancer cells that have spread to distant tissues and organs. Unlike chemo, they’re less likely to harm normal cells since they seek out specific cancer cell attributes, such as proteins that promote rapid cell growth, metastasis, and longevity.

Some targeted drug therapies enhance the effectiveness of other breast cancer treatments. Targeted drug therapy can be used to treat:

- Cancer caused by a BRCA gene mutation

- HER2-positive breast cancer

- HR-positive breast cancer

- Triple-negative breast cancer

Surgery for breast cancer

Treatment almost always includes some type of breast cancer surgery. Other breast cancer treatments, such as chemo or hormone therapy, may be needed before or after surgery.

Surgeries to remove breast cancer

Conventional breast cancer surgeries include:

- Breast-conserving surgery: This involves removing only the part of the breast that has cancer cells, as well as some normal tissue around this area. Your surgeon may refer to this procedure as a lumpectomy, partial mastectomy, quadrantectomy, or segmental mastectomy.

- Mastectomy: This involves removing your entire breast and sometimes other nearby tissue. A double mastectomy removes both breasts.

Wire or needle localization, also called wire-guided excision biopsy

Wire localization involves placing a thin, flexible wire into breast tissue to show your surgeon the exact location of cancerous tissue to be removed during breast-conserving surgery. Your surgeon uses an imaging device to guide the wire to the precise spot.

Using this wire to guide the removal of a tumor may be an option if the abnormal mass can’t be felt or it’s hard to find. Breast ultrasounds or mammograms are most often used to locate tumors, but a breast MRI can be used if necessary. The procedure is called stereotactic wire localization if a mammogram is used.

Surgery to remove affected lymph nodes

If cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes, an additional procedure to remove them can be performed at the same time as breast-conserving surgery, mastectomy, or in a separate procedure.

These procedures include:

- Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) or dissection (SLND): Your surgeon will inject a liquid that contains coated iron oxide particles or blue dye and/or radioactive substances into the tumor, the area around it, or your nipple. Your surgeon follows the path of the liquid to find and remove your sentinel nodes, which are the first lymph nodes into which cancer cells have likely spread beyond the breast.

- Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND): Your surgeon removes lymph nodes from your armpit to check for cancer spread. They may remove anywhere from 10 to 40 nodes, although they usually remove 20 or fewer.

What is the outlook for breast cancer?

In general, the earlier breast cancer is diagnosed and treated, the better your outlook and chances of long-term survival. Breast cancer awareness includes paying attention to possible warning signs of breast cancer and having an open and ongoing dialogue with your HCP about your risk factors and when and how often to screen for the disease. These conversations and screenings can be key to catching and treating breast cancer early.

Keep in mind that your personal outlook may differ from others. Many factors influence how your disease is likely to progress and your chances of survival.

What is the survival rate for breast cancer?

Survival rates for breast cancer describe the estimated percentage of people with the same type and stage who are alive five years after diagnosis. These rates can’t tell you what your specific chances of survival are, though they may offer estimates.

The outlook for long-term survival following an early breast cancer diagnosis remains positive. Around 60 percent of breast cancers diagnosed early have a 99 percent survival rate after five years, according to statistics for 2022 published by the American Cancer Society in CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.

The 5-year survival rate is 93 percent for stage II breast cancer and 72 percent for stage III. As cancer cells spread to distant parts of the body during stage IV, the 5-year survival rate declines to 22 percent.

What does it mean to live with breast cancer?

Having breast cancer can affect your life in many ways. These include physical, emotional, and practical challenges.

Physical changes due to breast cancer

Breast cancer symptoms and treatments can lead to physical changes and side effects that influence how you feel about your body. These may include:

- Changes to your body image after breast cancer surgery: These may result from altered size, shape, or loss of a breast or breasts. You may feel sensitive about your surgical scars or the size or shape of your body due to treatments. And you may not be as physically active as you once were due to breast cancer symptoms.

- Early menopause: Certain types of treatment may bring about the onset of menopause, which may cause uncomfortable symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, vaginal dryness, and low sexual desire.

- Fertility issues due to breast cancer treatments such as chemo

- Hair loss, a common side effect of chemo

Emotional changes stemming from breast cancer

You may experience profound emotions at any point during your cancer journey. You may also feel isolated or want to isolate yourself from others. Your partner, children, family, and friends may also have many strong feelings or they may not know what to say or how to comfort you. Remember that the emotional side of cancer is valid and real and is important to address along with any physical manifestations.

Practical changes related to breast cancer

Breast cancer treatments may strain your finances. Your work obligations may also need to take a temporary back seat. And you may need help at home with basic needs and daily tasks.

Tips to help with changes due to breast cancer

It’s important to find healthy ways to cope with these changes. This might mean different things to different people.

Don’t hesitate to seek help and guidance from your HCP during and after your cancer journey. You may also choose to lean on trusted loved ones or friends or seek support from communities of patients online or in your neighborhood.

You might choose to address challenges with the following strategies:

Talk with your HCP and expanded healthcare team about your needs and concerns. This might include discussing treatment options for menopause symptoms, including fertility concerns.

Build a team of specialists. You might meet with a registered dietitian nutritionist to learn about healthy eating strategies to boost your immune system, manage your weight, and ease symptoms such as fatigue and nausea. Consulting with a certified personal trainer can help you learn ways to stay active and fit when you have breast cancer. A social worker or case manager can help you locate community or healthcare resources to help you with your medical and personal needs at home.

Modify your grooming routine. You might wish to wear your makeup, do your nails, try a new hairstyle, and dress in your finest when you can. Or you may prefer to forego these during your treatment.

Consult with a plastic surgeon. You might consider breast reconstruction or prostheses to help restore the form and shape of your breast or breasts.

Seek out counseling. You might enlist a licensed mental health provider or a spiritual advisor. You may also want to join a support group (or refer your loved ones) to connect with others living through similar experiences.

Keep a journal. This can help you process your emotions. You may want to post to an online blog or on social media to update family and friends, or you can try expressing your thoughts and feelings about your breast cancer journey through art or music.

Remember to take unhelpful advice and discouraging or frightening information from friends and loved ones with a grain of salt. Although most people mean well, you are the captain of your own journey and as such you can choose what input to receive and what to leave to the side.

Featured breast cancer articles

Admoun C, Mayrovitz HN. The Etiology of Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer [Internet]. Published August 6, 2022

Ahn J, Suh EE. Body acceptance in women with breast cancer: A concept analysis using a hybrid model. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2023;62: 102269.

Alkabban FM, Ferguson T. Breast Cancer. StatPearls [Internet].Last updated September 26, 2022.

Allen I, Hassan H, Sofianopoulou E, et al. Risks of second non-breast primaries following breast cancer in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. 2023;25(1):18.

American Cancer Society. Alcohol Use and Cancer. Last updated June 9, 2020.

American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Risk Factors You Cannot Change. Last updated December 16, 2021.

American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Staging. Last updated November 8, 2021.

American Cancer Society. Hormone Therapy for Breast Cancer. Last updated January 31, 2023.

American Cancer Society. If You Have Breast Cancer. Last updated January 5, 2022.

American Cancer Society. Immunotherapy for Breast Cancer. Last updated October 27, 2021.

American Cancer Society. Inflammatory Breast Cancer. Last updated March 1, 2023.

American Cancer Society. Lifestyle-Related Breast Cancer Risks. Last updated September 19, 2022.

American Cancer Society. Phyllodes Tumors of the Breast. Last updated June 15, 2022.

American Cancer Society. Survival Rates for Breast Cancer. Last updated March 1, 2023.

American Cancer Society. Targeted Drug Therapy for Breast Cancer. Last updated March 3, 2023.

American Cancer Society. Treatment of Inflammatory Breast Cancer. Last updated April 12, 2022.

American Cancer Society. Treatment of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Last updated April 12, 2022.

American Cancer Society. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Last updated March 1, 2023.

Breastcancer.org. Know Your Risk: Breast Cancer Risk Factors. Last updated February 21, 2023.

Breastcancer.org. Know Your Risk/Breast Cancer Risk Factors: Smoking. January 4, 2023.

Cariolou M, Abar L, Aune D, et al. Postdiagnosis recreational physical activity and breast cancer prognosis: Global Cancer Update Programme (CUP Global) systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2023;152(4):600-615.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Basic Information About Breast Cancer. Last reviewed September 26, 2022.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breast Cancer in Men. Last reviewed September 26, 2022.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breast Cancer in Young Women. Last reviewed September 27, 2021.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disparities in Cancer Deaths. Last reviewed October 18, 2022.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What Are the Risk Factors for Breast Cancer? Last reviewed September 26, 2022.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What Does It Mean to Have Dense Breasts? Last reviewed September 26, 2022

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What Is Breast Cancer? Last reviewed September 26, 2022.

Cleveland Clinic. Breast Cancer. Last reviewed January 21, 2022.

Deb S, Chakrabarti A, Fox SB. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers in familial breast cancer. Cancers. 2023;15(4):1346.

DePolo J. Understanding Your Pathology Report: Breast Cancer Stages. Breastcancer.org. Last updated November 18, 2022.

Gaba F, Blyuss O, Tan A, et al. Breast cancer risk and breast-cancer-specific mortality following risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA carriers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers. 2023;15(5):1625.

García-Chico C, López-Ortiz S, Peñín-Grandes S, et al. Physical exercise and the hallmarks of breast cancer: A narrative review. Cancers). 2023;15(1):324.

Iacopetta D, Ceramella J, Baldino N, Sinicropi MS, Catalano A. Targeting breast cancer: An overlook on current strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3643.

Jia T, Liu Y, Fan Y, Wang L, Jiang E. Association of healthy diet and physical activity with breast cancer: Lifestyle interventions and oncology education. Front Public Health. 2022;10:797794.

Levy R. What Does a Breast Lump Feel Like? Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Last updated December 5, 2022.

Manouchehri E, Taghipour A, Ghavami V, Ebadi A, Homaei F, Latifnejad Roudsari R. Night-shift work duration and breast cancer risk: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):89.

Mayo Clinic. Breast Cancer. Last updated December 14, 2022.

Mayo Clinic. Recurrent Breast Cancer. Last updated July 2, 2022.

McVeigh UM, Tepper JW, McVeigh TP. A Review of breast cancer risk factors in adolescents and young adults. Cancers. 2021;13(21):5552.

MedlinePlus. BRCA Genetic Test. National Library of Medicine. Last updated September 12, 2022.

MedlinePlus. Breast Cancer. National Library of Medicine. Last updated September 12, 2022.

MedlinePlus. Breast Cancer. National Library of Medicine. Last updated May 28, 2021.

MedlinePlus. TP53 Genetic Test. National Library of Medicine. Last updated June 24, 2021.

National Cancer Institute. Angiosarcoma. Published February 27, 2019.

PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. Breast Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Published March 10, 2023.

PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board. Male Breast Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. Published March 10, 2023.

Pérez-Bilbao T, Alonso-Dueñas M, Peinado AB, San Juan AF. Effects of combined interventions of exercise and diet or exercise and supplementation on breast cancer patients: A systematic review. Nutrients. 2023;15(4):1013.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7-33.

Starek-Świechowicz B, Budziszewska B, Starek A. Alcohol and breast cancer. Pharmacol Rep. 2023;75(1):69-84.

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249.

Thomas JA, Miller ER, Ward PR. Lifestyle interventions through participatory research: A mixed-methods systematic review of alcohol and other breast cancer behavioural risk factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(2):980.

U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: Data Visualizations. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Cancer Institute. Last updated November 2022.

Vegunta S, Kuhle CL, Vencill JA, Lucas PH, Mussallem DM. Sexual health after a breast cancer diagnosis: Addressing a forgotten aspect of survivorship. J Clin Med. 2022;11(22):6723.

World Health Organization. Breast Cancer. Last updated March 26, 2021.

Metzger-Filho O, Ferreira AR, Jeselsohn R, et al. Mixed Invasive Ductal and Lobular Carcinoma of the Breast: Prognosis and the Importance of Histologic Grade. Oncologist. 2019;24(7):e441-e449.

American Cancer Society. Invasive Breast Cancer (IDC/ILC). Last Revised: November 19, 2021.

Bergeron A, MacGrogan G, Bertaut A, et al. Triple-negative breast lobular carcinoma: a luminal androgen receptor carcinoma with specific ESRRA mutations. Mod Pathol. 2021;34(7):1282-1296.

American Cancer Society. Genetic Counseling and Testing for Breast Cancer Risk. Last Revised: December 16, 2021.

National Cancer Institute. Reproductive History and Cancer Risk. Reviewed: November 9, 2016.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Hormonal Contraception and Risk of Breast Cancer. Practice Advisory. January 2018.

American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Hormone Receptor Status. Last Revised: November 8, 2021.

American Cancer Society. Angiosarcoma of the Breast. Last Revised: November 19, 2021.

National Cancer Institute. Cancer Statistics. Updated: September 25, 2020.