Updated on December 7, 2023

Heart disease is the leading cause of death among women in the United States, totaling more than 400,000 lives lost each year. That’s one death every 80 seconds, according to the American Heart Association (AHA). But the epidemic of heart disease affects Black women more severely than it does any other group.

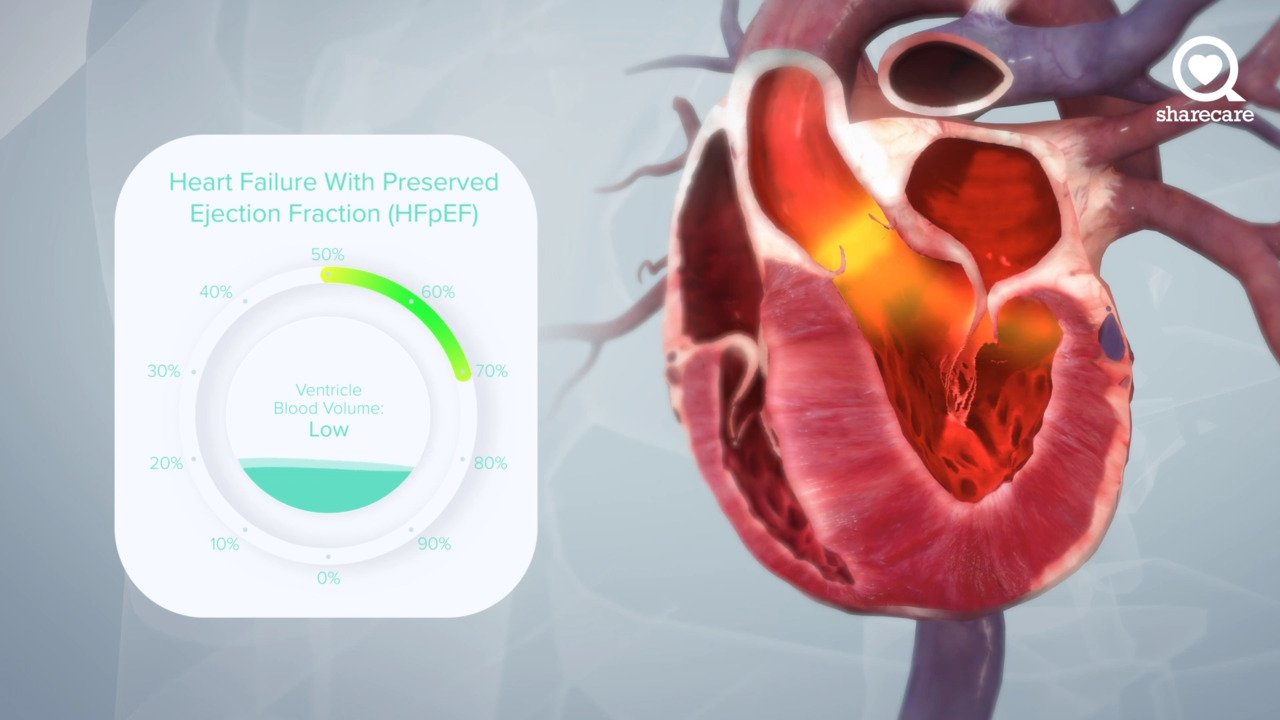

In fact, nearly 59 percent of Black women aged 20 and older have cardiovascular disease (CVD), compared to 42 percent of white women, according to data from the AHA published in 2022. (Cardiovascular disease comprises conditions that affect the heart and blood vessels, including coronary artery disease, heart failure, and stroke.)

Rates of high blood pressure, also known as hypertension, follow a similar pattern. About 58 percent of Black women aged 20 and older have high blood pressure, compared to 41 percent of white women. (High blood pressure is a major risk factor for CVD.) Black women’s risk of stroke, meanwhile, is nearly twice that of white women.

Black women die more frequently from heart disease than white women do, with a mortality rate that is at least 30 percent higher. They also have nearly twice the rate of hypertension-related deaths. All told, more than 50,000 Black women in the U.S. die each year from cardiovascular diseases.

What accounts for these striking disparities?

Spotlighting the effects of racism on health

One major factor behind this elevated risk of heart disease that researchers are exploring is the experience of racism. Black people often face discrimination in a variety of areas of life, including housing, education, employment, and interactions with the healthcare and criminal justice systems. Structural racism that pervades these parts of society can lead to unequal access to healthy food, healthy living environments, and preventive health resources.

Racism can also manifest in the form of microaggressions. These subtle expressions of racism may take the form of everyday comments or interactions. Over time, the accumulation of microaggressions can chip away at one’s sense of well-being and contribute to elevated levels of harmful stress.

Research has shown that the kind of chronic, toxic stress that results from confronting racism on a daily basis has an impact on mental and physical health. It may raise Black people’s risks for not only depression and anxiety, but also conditions including high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke.

A study published in November 2023 in JAMA Network Open looked directly at the relationship between racism and stroke among Black women. Researchers tracked 48,375 Black women over the course of 22 years, asking them every two years about racism they had experienced on a personal level. The women had no cardiovascular disease at the start of the study, but researchers found that women who reported experiences of racism in employment, housing, and interactions with police had an estimated 38 percent increased risk of having a stroke, compared to women who reported no such experiences of racism.

As the authors point out, the stress of experiencing racism may contribute to elevated stroke risk by increasing inflammation in the body, harming the lining of blood vessels, raising blood pressure, and altering the function of stress hormones.

In a vicious cycle, such stress may also make it harder to manage conditions caused in part by that stress.

A 2018 study published in Preventive Medicine Reports found that 84 percent of Black women with high blood pressure didn’t take their medications as prescribed and 59 percent did not follow healthy lifestyle changes, such as diet and exercise, to help manage their condition. The authors reported that this lack of adherence may be due to elevated levels of stress. Stress, for example, can make it harder to exercise regularly and may lead to eating unhealthy foods (such as those high in sugar and fat) as a coping mechanism.

Other contributors to increased heart disease risk

Experts identify several other factors that may contribute to the increased risk of heart disease among Black women.

Barriers to care

Black women encounter barriers to receiving quality health care, and specialty care in particular, compared to members of other groups, says Vinayak Manohar, MD, an interventional cardiologist in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Research also suggests that Black women have a disincentive to seek health care: distrust of the healthcare system. This is due, in part, to a legacy of negative experiences that Black people in the U.S. have had with healthcare providers (HCPs) and the healthcare system.

Studies have also shown that many HCPs carry implicit bias against Black patients, particularly Black women. As a result, Black women often don’t receive the same-quality treatment that white women do. Among other outcomes, this contributes to the 2.6-times-higher rate of maternal mortality that Black women experience relative to white women, as well as fewer preventive screenings for heart disease and other conditions.

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status may contribute to the lack of quality care in several ways.

U.S. Census Bureau data show that 17 percent of Black people live in poverty, compared with 8.6 percent of the non-Hispanic white population. Even with health insurance coverage, obtaining quality health care can be very expensive, and increasingly so. People who live in poverty also have higher risks of heart disease and diabetes. Specifically, research has shown that the chronic stress that comes from living in poverty is linked to inflammation that directly hurts blood vessels.

Environmental exposures

Black people are more likely than white people to live in areas with greater exposure to toxic environmental chemicals, whether from air pollution or living in proximity to highways and industrial or agricultural sites. Many such chemicals—including lead, mercury, heavy metals, and pesticides—can contribute in various ways to the development of heart disease.

Pregnancy complications

Pregnancy issues are more common among Black women than they are among white women. These include high blood pressure during pregnancy, gestational diabetes, pre-term delivery, low birth weight, and pregnancy loss. These issues, known as adverse pregnancy outcomes, increase a woman’s risk of developing cardiovascular disease.

The added effects of high blood pressure and obesity

Dr. Manohar cites two additional “stand-out” risk factors that are more prevalent, tend to be more severe, and develop earlier in life for Black women relative to white women: high blood pressure and obesity.

More than half of Black women aged 20 and older have high blood pressure and 78 percent of Black women are overweight or obese. It’s the highest rate of obesity among any group in the U.S. High blood pressure and obesity, which significantly raise the risk for coronary artery disease, contribute to other major health problems, including chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes, which is itself a risk factor for heart disease, Manohar says.

There are a variety of reasons why Black women have such disproportionately high rates of obesity. One has to do with the greater likelihood that Black women live in “food deserts.” These are areas where fresh, whole foods are hard to find and where available options tend to include ultra-processed foods (such as fast food and packaged food) that contribute to the development of obesity.

Research has also examined the link between diet and high blood pressure. A 2018 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association followed nearly 6,900 American men and women over the age of 45 for a period of 10 years to identify risk factors associated with high blood pressure. The researchers found that a high-sodium diet rich in fried, processed, fatty foods and sugar-sweetened beverages was the largest factor contributing to higher rates of hypertension among Black people when compared to white people.

Reducing the risks that Black women face

As a starting point to helping to improve the health of Black people, many experts agree that the medical establishment must confront and reckon with the racism—implicit and explicit—that has pervaded American society and the healthcare system for many years. For example, in December 2023, the New England Journal of Medicine published the first in a series of articles investigating the “various aspects of the biases and injustice that the Journal has helped to perpetuate in its more than 200 years.”

Many experts also feel that the medical community must work harder to educate Black women about the risks of hypertension, heart disease, and stroke. Research has shown, for example, that Black women are less likely than white women to be aware of heart attack symptoms. It shouldn’t be the sole responsibility of individual patients, however, to cure themselves of ills with complex origins that are often engrained in the structure of society.

Lifestyle changes to lower heart disease risk

As the hard work against racism proceeds, Black women can take certain steps to help lower their risk of cardiovascular problems. These include the following:

Watch blood pressure levels. Monitoring is key to detecting changes in heart health. High blood pressure is considered 130 mm Hg and higher for systolic blood pressure (the top number in a blood pressure reading) or 80 mm Hg and higher for diastolic blood pressure (the bottom number). Blood pressure is considered elevated at levels above 120 mm Hg systolic.

Readings can be taken at home, at many pharmacies, or at an HCP’s office. If you take medication to manage blood pressure, be sure to stick to it as closely as possible and ask your HCP if you have any questions about your prescription. Research suggests that education programs located at the community level—such as in churches and not necessarily in HCP offices—may benefit Black women in particular.

Engage in regular physical activity. To maintain a healthy weight and improve heart health, it’s important to try to move for at least 30 minutes or more each day, aiming for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise each week. Even a regular habit of brisk walking can help to lower risk.

It can be challenging to get regular exercise if parks are hard to find or outdoor spaces are unsafe for walking. But there are still ways to get the daily recommended 30 minutes of physical activity even while staying inside. Simple workout routines can be done indoors and even doing household chores can help burn calories.

Know cholesterol levels. Excess cholesterol and fat in the bloodstream can narrow arteries and increase the likelihood of a heart attack or stroke. Generally speaking, people without heart disease should aim for a total cholesterol level of less than 200 mg/dl. People with heart disease may need to set lower levels. It’s important to have regular testing to keep an eye on those numbers, starting at age 20 if possible.

Quit smoking and using tobacco products. About 14 percent of Black women smoke, which is a major risk factor for heart disease. While Black adults try to quit smoking more frequently than white adults, they often run into barriers in their efforts. These include lack of access to counseling programs and medication that can help with quitting. The CDC offers help for quitting smoking, including free coaching and other resources.

Get tested for diabetes. Black adults are 60 percent more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes than non-Hispanic white people and they tend to develop it earlier in life. Since an estimated two-thirds of people with type 2 diabetes die of heart-related complications, it's important to be evaluated for the disease, which can be detected with a simple blood test.

Manage health conditions. Lupus, an autoimmune condition that causes inflammation throughout the body, can contribute to heart disease. It’s also more common in Black women. If you have lupus, it’s important to work with your HCP to manage the condition to help lower the risk of heart-related complications.

The same goes for rheumatoid arthritis, which also increases one’s risk for heart disease. Black women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) also have a higher risk of heart disease and stroke compared to white women. PCOS can be managed with medication and maintaining a healthy weight, which also helps reduce the risk of heart disease.

Prioritize healthy eating. It can be hard to prepare fresh meals each day of the week but emphasizing healthy dining whenever possible can go a long way toward reducing the risk of heart disease. That means reducing processed foods as much as possible and adding more fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and beans and legumes to your plate. Produce doesn’t have to be farm-fresh to be wholesome. Frozen and low-sodium canned varieties pack levels of nutrients and heart-healthy fiber that are comparable to fresh fruits and veggies.

A good rule of thumb for mealtime: Fill half your plate with fruits or vegetables, one quarter with a whole grain (like brown rice), and another quarter with a lean protein, whether from animal sources (like chicken, fish, or lean cuts of meat) or vegetable sources (such as beans or tofu).

None of these changes have to be made all at once, and some risk factors, such as age or a family history of early heart disease, can’t be changed. Start gradually, tackling each risk factor you can control one at a time to help lower the risk of heart disease or stroke.

It's also important to women know the signs of a heart attack, which can differ from those seen in men. In addition to typical symptoms—such as uncomfortable pressure in the center of the chest or pain that radiates to the shoulder, neck, and arms—women may experience sharp pain in the neck, back, and jaw. They may also feel nausea, dizziness, unusual fatigue, shortness of breath, and lightheadedness. If you believe you're experiencing a heart attack, dial 911 immediately, because fast treatment is crucial to survival.