5 reasons to talk to your doctor about shingles

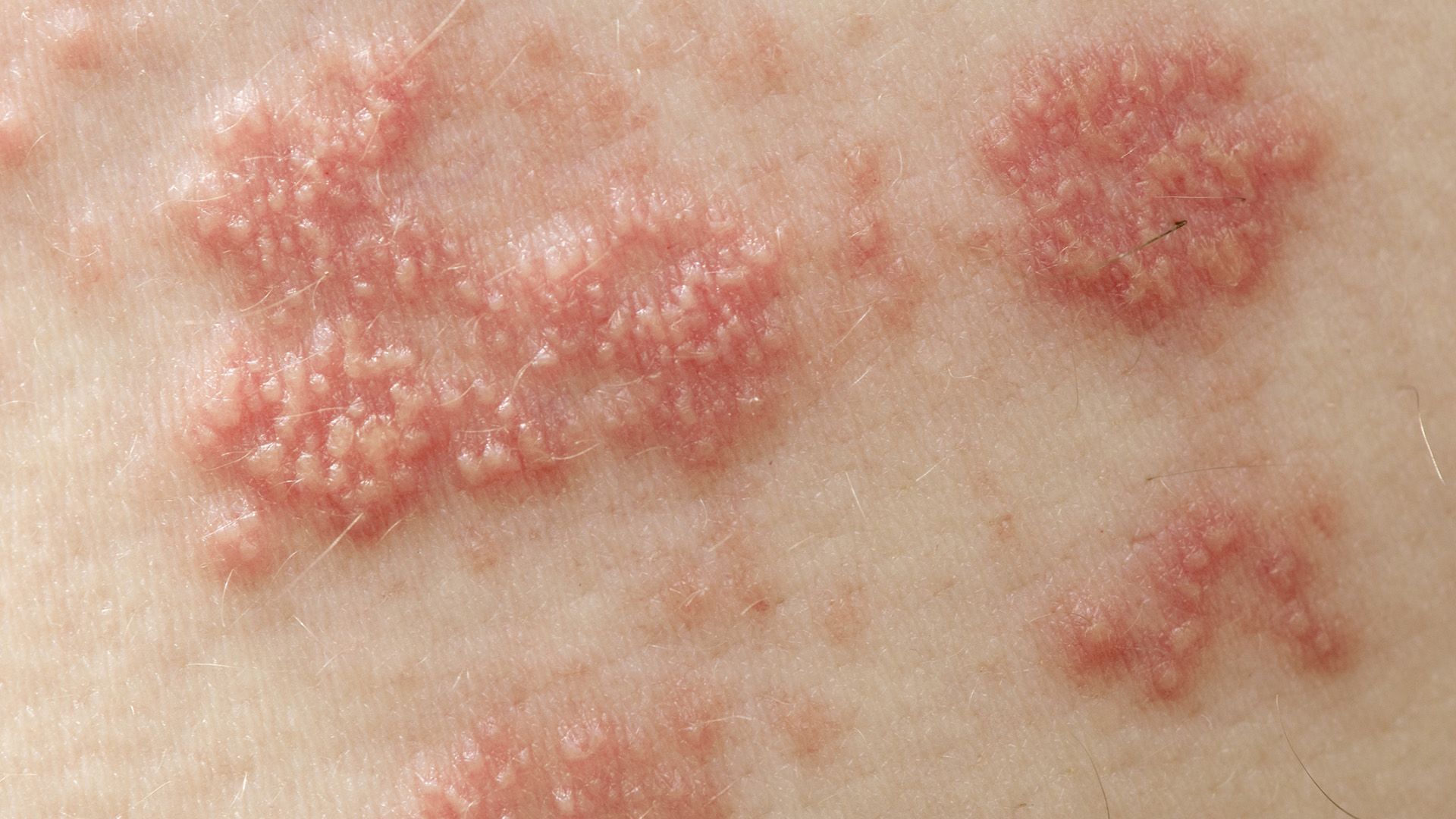

Essential questions about the painful, blistering rash known as shingles.

If you’ve ever had chickenpox, you already have the virus that can cause a shingles infection. The two conditions are both caused by the varicella-zoster virus (also referred to as VZV). After you’ve recovered from chickenpox, VZV remains in your body, dormant in the tissues of your nervous system. Years later, the virus can reactivate, causing shingles.

Shingles is a painful, blistering rash. It typically appears on one side of the body, following the path of a nerve fiber. It is often preceded by itching, tingling or pain in the days before the rash appears. For the first 7 to 10 days, the rash consists of fluid-filled blisters. After 7 to 10 days, the blisters scab over, but it may take a few more weeks for the rash to clear up completely.

Here are five reasons you should speak to your healthcare provider about shingles.

You (probably) already have VZV

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are about 1 million cases of shingles in the United States each year. One in three Americans will have shingles at some point during their lifetime.

VZV, the virus that causes both chickenpox and shingles, is even more common. It’s estimated that 99.5 percent of people born in the U.S. who are 40 years and older have had chickenpox. This means that almost everyone age 40 and up carries the virus with the potential to cause a shingles infection.

Shingles can cause complications

The most common complication of shingles infection is postherpetic neuralgia, or PHN for short. PHN is nerve pain that persists after the rash from shingles infection has cleared up. This nerve pain occurs in the same location on the body that the shingles rash occurred. It can feel different to different people. The pain can be sharp and sudden, constantly burning and aching, or itchy, numb and extremely sensitive to touch.

While a typical shingles rash clears up within two to four weeks, PHN usually lasts between one and three months. For 10 to 20 percent of people who experience PHN, however, the pain lasts a year or longer. In rare cases, the pain can last a decade.

Your risk increases with age

Children, teenagers and adults of all ages all get shingles. But the risk increases greatly after age 50. According to reports, people over 50 account for nearly 70 percent of shingles infections and shingles-related complications like PHN.

Why does the risk of having shingles increase with age? Your immunity to VZV, which began when you first got chickenpox, becomes less effective as you get older. This is also why shingles and PHN tend to be more severe the older you are.

Having a compromised immune system at any age raises your risk of shingles and PHN. A weakened immune system can result from medical conditions like cancer and HIV. Certain medications also suppress immunity and put you at risk for shingles. These include steroids and TNF (tumor necrosis factor) inhibitors, which treat autoimmune conditions such as psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis.

You can get shingles again

Most people have shingles only one time. But having shingles once does not mean you won’t have it again. There is not much information about the number of patients or percentage of patients who have had multiple episodes of shingles. There are, however, plenty of reported cases of people who have had shingles a second time. Some have even had shingles a third time.

Because of the risk of recurrence, the CDC recommends a shingles vaccine for anyone who has had shingles before. Getting vaccinated can lower the risk of having shingles again.

You can prevent shingles

The only way to prevent shingles is by getting a shingles vaccine. The CDC recommends the shingles vaccine for people age 50 and up, including those who have had shingles already. This also includes people who received a previous version of the shingles vaccine, since there is a newer vaccine that is better at preventing shingles.

You should discuss some things with your healthcare provider that could affect your decision to get the shingles vaccine. These include your medical history, known allergies and medications you are taking. If you have recently been sick (with the flu, for example) you may need to delay your shingles vaccine. People who are pregnant, breastfeeding or planning to become pregnant will also need to delay the vaccine.

You can get the shingles vaccine at your healthcare provider’s office or at your local pharmacy. Remember to contact your insurance provider about coverage before getting vaccinated.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “About Shingles (Herpes Zoster).” June 26, 2019. Accessed October 9, 2020.

Mayo Clinic. “Shingles.” October 6, 2020. Accessed October 9, 2020.

Merck Manual Consumer Version. “Shingles.” April 2020. Accessed October 9, 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Get the New Shingrix Vaccine If You Are 50 or Older.” July 2, 2019. Accessed October 9, 2020.

UpToDate.com. “Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of herpes zoster.” Current through September 2020. Accessed October 9, 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Shingles: Clinical Overview.” August 14, 2019. Accessed October 9, 2020.

Mayo Clinic. “Postherpetic neuralgia.” November 1, 2018. Accessed October 9, 2020.

P Sampathkumar, LA Drage, & DP Martin. “Herpes Zoster (Shingles) and Postherpetic Neuralgia.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings. March 2009, 84(3), 274–280.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Shingles Burden and Trends.” August 14, 2019.

Shawn Bishop. “Risk of Shingles Increases with Age, but Vaccine is Available.” Mayo Clinic News Network. February 12, 2010.

BP Yawn, PC Wollan, et al. “Herpes Zoster Recurrences More Frequent Than Previously Reported.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings. February 2011, 86(2): 88–93.

Urmila Parlikar. “Shingles can strike twice. Will the shingles vaccine help?” Harvard Health Publishing. March 2, 2011.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “What Everyone Should Know about Zostavax.” January 25, 2018. Accessed October 9, 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Shingles Vaccination.” January 25, 2018. Accessed October 9, 2020.

Mayo Clinic. “Shingles vaccine: Should I get it?” September 18, 2020. Accessed October 9, 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Signs and Symptoms.” July 1, 2019. Accessed October 13, 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Shingles.” June 26, 2019. Accessed October 13, 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Complications of Shingles.” July 1, 2019. Accessed October 13, 2020.

T Mallick-Searle, B Snodgrass, & JM Brant. “Postherpetic neuralgia: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and pain management pharmacology.” Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2016, 9, 447–454.

WD James, DM Elston, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 19, 362-420.e8. 2020. Elsevier.

Carrie DeVries. “Is Your Medication Raising Your Risk for Shingles?” Arthritis-Health.com. October 28, 2014.

Featured Content

article

video

article

video

article